Introduction

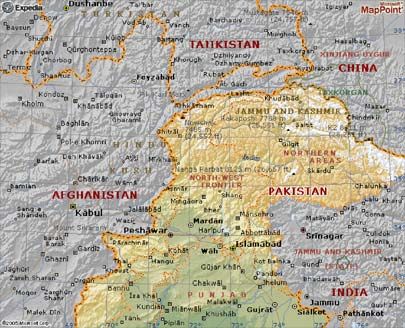

On 8th October 2005 an earthquake at 7.6 on the Richter scale tore across the fault line in Northwest Pakistan. In minutes 100 000 people lost their lives and 70 000 (est.) were injured. This occurred in an area of severe poverty and poor infrastructure, to a stratum of society without political status or national power. The towns and villages were densely populated and housing cheaply constructed or perched on mountainsides. The devastation was absolute and initially under-reported.

I watched a surgeon on the BBC News telling a reporter that you could not put dollars on wounds – he needed doctors. Another told reporters that he had amputated 100 limbs so far. I joined a team of doctors from Yorkshire and went to Pakistan arriving 7 days after the earthquake. I arrived to find hundreds of severely injured patients, the majority needing plastic surgical reconstruction and myself as the only plastic surgeon in the region.

Our team arrived at Abbottabad one week after the earthquake. Abbottabad is 50km from the capital Islamabad and 50km southwest of the earthquake epicentre. The town had sustained earthquake damage. This was the nearest large town to the victims and the only one with adequate infrastructure for reconstructive surgery. It had become flooded with injured patients, filling the corridors of the University Hospital. Whatever our preconceived plans, on arrival, having witnessed the chaos and enormity of the problem, our team had to focus on the immediate surgical treatment of casualties and calling in more plastic surgeons.

Why the victims needed plastic surgery

The public concept of plastic surgery equates to cosmetic surgery, but in fact plastic and reconstructive surgery is a speciality based on the techniques used to reconstitute parts and restore function. The restoration of appearance is a secondary goal to function. Injuries to limbs have two components. There is the bony injury and the soft tissue injury. Severe injuries particularly of the types seen in earthquake zones not only break or shatter bone but also destroy the flesh covering these bones. As a plastic surgeon my job is to rebuild the soft tissue support. This starts by cleaning and then debriding a wound to control infection and remove dead tissue. Then using a range of techniques healthy flesh is brought in to close the wound, creating an environment in which bone healing can occur. These techniques may be simple direct skin closure, skin grafting, local flaps (an area of flesh is rotated into the tissue defect from an adjacent healthy area), a distant flap (an area of healthy of flesh is used to cover the defect by attaching the defect to the healthy area temporarily) and a free flap in which microsurgery is used to transfer a piece of tissue from one part of the body to another. In addition damaged nerves and tendons are repaired, as without these function will not be present. This approach is essential as open complex injuries of this type will become infected, further extending damage and leading inevitably to amputation. It is important at this stage to recognise and preserve tissues that can be salvaged, whether that be a particular nerve or the whole limb. In the aftermath of the earthquake hundreds of victims were left with severe life or limb-threatening wounds. The infrastructure to treat them even before the earthquake would have been extremely limited. Add to this that the majority had no status, funds or fixed abode and that public healthcare is grossly under-resourced and riddled with corruption. The pending harsh winter added a sinister deadline. Initially mainly orthopaedic and general surgeons set about debriding wounds, fixating bones and amputating limbs. The evidence that I consistently found was that these surgeons were inexperienced. These would have been difficult injuries to treat in the UK and would have required experienced consultant input. No plastic surgeons were available. The reasons for this are as follows:

- Few understood the size of the problem

- Few understood the need for plastic surgery to reconstruct these large tissue defects

- Pakistan has very few plastic surgeons and only one group was within 100 miles. They were snowed under with transferred patients. Others were unwilling to travel and work in this area initially.

There were very few local sites for such surgeons to work. This meant that patients remained untreated and that their wounds were rapidly becoming infected. I had put together supplies and instruments for the task and our total relief cargo approached 1 tonne on the first trip.

The surgical problem

It is important to understand the nature of the injuries sustained by the earthquake victims and the section shows some of those whom I treated.

Danesh, age approx 10

I found Danesh in the crowded corridor of the University Hospital. He had been waiting for days for treatment along with many hundreds of other patients. His surviving family thrust x-rays into my hands and pleaded with me to help him. Danesh’s hands were crushed by a large piece of masonry and helpers had to pull hard to extricate him from the rubble. The bones were fractured, the skin was stripped off and he was waiting for a planned amputation of both his hands. He was terrified. At surgery it was clear to me that his hands were salvageable. Although he had multiple fractures and loss of skin the basic units of the hand – the tendons, nerves and bones were present. I restored the skin to the space between the thumb and his index finger using a distant flap from his groin. The conditions available did not support microsurgery as an option as it requires sophisticated, expensive facilities and experienced specialist in-patient nursing. I repaired the fractures and grafted the remaining areas of skin loss.

My plastic surgical colleague, Col. Mamoon of the Pakistan Army kindly took over his care in his own specialist unit and with his help both Danesh’s hands were salvaged. His progress was reported in The Independent newspaper on 24 November 2005.

Sajjad, age approx 10

Sajjad’s case exemplified a disturbing aspect of treatment in these situations. Sajjad sustained an open fracture of his leg which was treated by an unknown surgeon. Instead of fixing the fracture directly, this surgeon inexplicably removed a large portion of the bone and replaced it with a rod of adjacent bone which was inappropriate in size and calibre. The wound was infected and open. Prospects were bleak for Sajjad because of the chronic infection (I treated Sajjad on December 5th 2005 on my second trip). He had no appetite, had lost weight and was suffering from intermittent high temperatures and malaise due to blood spread of the infection.

Over the course of a week and 3 operations, I cleaned out the infection. Our team gave him appropriate antibiotics and nutritional support. We encouraged his family to feed him as much as possible and him to eat as much as possible. When he was stronger I moved healthy muscle over his fracture site and in this way closed the wound. I handed his subsequent bone care to a competent local orthopaedic surgeon at the military hospital with whom I worked closely. He is making good progress.

There were many more patients with severe injuries. Patients with large areas that were unhealed, fractures open to the air, infected fractures; amputation stumps that were open, agonisingly painful, many of these were young children.Over the period of two trips our team treated over one hundred patients surgically, Many of these were facing amputation.Wherever possible we passed on our knowledge to our Pakistani colleagues and indeed learnt from them.Our team did not leave Pakistan on either of our relief trips without ensuring as best we could that all the patients treated had their aftercare organised.

Kulsoom

Kulsoom was also awaiting amputation of her hand. She had lost her little, ring and middle fingers and there was simply not the expertise to heal the wound. It was clear to me that her hand had a functioning thumb and index finger and as such would infinitely more useful than an amputation stump.

Repaired the fractures that were present and carried out a skin cover procedure. Kulsoom’s hand was salvaged.

Asad

Asad is lucky to be alive. A local surgeon asked me to look at him before I left Pakistan at the end of my first trip. He was at the military hospital and although I had visited this hospital, the volume of work where I was based prevented me from operating at this site. Our practice was to transfer patients over to our site if they needed specialist input. My plan that evening was to say my goodbyes and hand over aftercare instructions for some patients that I had treated to colleagues I had got to know and trust at the military hospital. He had an exposed skull fracture, a fractured rib protruding out of a right chest wound, a large wound to his left arm and multiple fractures and tendon injuries to his right hand. These severe internal right hand injuries had not been noticed and someone had already sutured the wound. There was no anaesthetist or operating list for Asad’s treatment that day. He was only a small child, had multiple wounds and was facing an amputation of his left arm and a crippled right arm. My opinion was that his limbs could be salvaged to a very functional level and all his other wounds closed with the right care. I made my wishes known to Colonel Innayat, (Consultant Anaesthetist and Head of Theatres). The Colonel agreed to anaesthetise this patient himself and together we worked until 2am repairing the damage. Asad’s wounds healed and he did not require amputation.

Pre-op Final dressings

Post-op, just waking

Surgical Relief Trip 15th-29th October 2005

My goals were as follows:

Individual patients

- To prioritise those whose need was most urgent.

- To provide reconstructive surgery to the victims to save lives and salvage limbs.

- To rapidly train and use those members of our team with surgical experience in simple wound debridement and closure so that I could use my time efficiently treating those who most needed my expertise.

- To document the work carried out and arrange safe aftercare for when we left.

Local

Establish links with key local doctors and officials to establish a facility that could provide reconstructive surgery locally (and hence accessible to patients) and ensure that it was staffed with experienced plastic surgeons when I left. Establish the limits and capacity of local hospitals and identify a facility that cases requiring advanced and more complex or longer-term care could be transferred to.

Regional

In conjunction with the public health service, the military health service and key members of the Pakistan Association of Plastic Surgeons, to form a strategy for the delivery of reconstructive surgery in the area.

International

To get help. Pakistan needed to know that there were no other reconstructive surgeons here and why they were so badly needed. To enlist the help of surgeons whom I knew had the appropriate expertise. I contacted my UK colleagues through the British Association of Plastic Surgeons. To set up a rota of UK plastic surgical teams to come to Abbottabad to continue the work that I had started as the need would be critical for the next 3 months. These goals were achieved and are summarised in my report of 31 October 2005 (appendix 1).

Surgical Relief Trip 3rd-15th December 2005

My goals were as follows

Individual patients

- To continue the work that I had been carrying out previously as many patients remained untreated or required secondary surgery

- To spend one week carrying out this work on a group of patients that a charitable organisation run by Dr Ghazala (a key local doctor) had collected and who needed urgent treatment. The charity had purchased the use of a staffed ward and theatres at the Women and Children’s Hospital, Abbottabad for this purpose.

- To spend one week at the CMH operating on further patients in line with the rota that I had set up.

- To carry out surgical procedures on patients that the non-surgical part of our team working in camps were sending to Abbottabad

- Arrange the aftercare of these patients.

It was clear to me on my first trip that reconstructive work would need to continue for many weeks, I gave a presentation to the Winter Meeting of the British Association of Plastic Surgeons (appendix 2) to get some help. My colleagues and I put together a rota of experienced UK plastic surgeons to work for 2 weeks at a time at the Central Military Hospital (CMH) in Abbottabad. On my first trip I had established credibility as a reconstructive surgeon – nobody had been successfully salvaging limbs and closing these difficult wounds in Abbottabad before our team arrived. As a result, the Army, who ran the cleanest and most efficient hospital in Abbottabad, allowed us the use of their facilities including accommodation and support for the visiting teams. This was vital for an ongoing relief effort. The remainder of my goals were to gather information on the amount of work that remained and the status of the facilities available (many, normally private hospitals, had only been opened to earthquake victims in the immediate aftermath). As the number of surgical patients began to fall, our team shifted focus to primary care in the camps.

Summary

When I left on 15th December 2005 after 2 relief trips the following had been achieved

1. Operative facility established and used for 3 days…

at The Ayub Medical Complex (University Hospital), Abbottabad. This facility was abandoned due to safety concerns following a severe aftershock. It is currently back in use. Contacts made with:

- Dr Huma Jadun – (Senior Consultant and co-charity worker with our team)

- Mr Khalil Sattar (Industrialist and co-charity worker)

- Mr Sattar provided us with accommodation, transport, storage, vital personnel and made us very welcome.

3. Operative facility established for visiting UK surgeons at CMH Abbottabad…

This military hospital was key in providing care for the ensuing months after the earthquake. I operated here for my last week.Contacts made with:

- Col Amjad (Unit Commander)

- Col Innayat (Head of Theatres)

- Col Shafquat (General Surgeon)

- Col Asim (Orthopaedic Surgeon)

- Dr Samira Agarawal (Plastic Surgeon, Pakistan)

- Dr Ayub Agarawal (Consultant Paediatric Surgeon, Pakistan)These doctors had coordinated and provided care prior to our arrival and were crucial in providing continuity of care and aftercare.

5. Operative facility established and used for 4 days at Women and Children’s Hospital, Abbottabad…

Contacts made with:

- Dr Ghazala (Consultant and co-charity worker with our team)

- Dr Amir (Senior Resident W&C Hospital)

2. Operative facility established and used at the Frontier Medical College…

(a private medical school run by Drs Khan and Shahina), for 9 days after leaving the damaged University Hospital.

4. Tertiary referral base made at the CMH Rawalpindi…

This is the regional plastic surgery unit and is run to a specification that is second to none by Col Mamoon – an internationally respected plastic surgeon and accomplished microsurgeon. No such facility existed locally and these take years to establish. Col Mamoon kindly accepted for treatment patients that we had no way of treating in Abbottabad.

6. Links established between the British and Pakistan Associations of Plastic Surgeons…

for reciprocal training and the exchange of knowledge (appendix 3).

7. Patients Treated

15th – 29th October 2005

- 100 in-patients

- 70 operative procedures

3rd – 15th December 2005

- 57 operative procedures

In a typical 4 weeks in the UK, I would expect to operate on 30 – 60 emergency and elective patients. The majority of the patients that we treated would have suffered amputation or severe disability and in most these sequelae have been avoided. In parallel to this work, I participated in planning the wider strategy of our group. This consisted of ways to introduce much needed primary care to the se people, the establishment of a limb-fitting centre and the first steps to introduce the system of advanced trauma and life support training to Pakistan. My own longer-term aim is to return to the area at regular intervals to train willing local doctors in reconstructive approaches to limb trauma. This will require building on the relationships made with local doctors, the British and Pakistan Association of Plastic Surgeons, Pakistan Government and Military Officials. These projects continue.

Conclusion & Acknowledgements

The earthquake in NW Pakistan was a devastating event. The victims and their families showed strength, courage and dignity in extreme circumstances. My team and I built up a strong level of trust with them by working until we quite literally were ready to drop at times and they put their faith in us. I feel privileged that my own circumstances put me in a position to help them. The earthquake in NW Pakistan was a devastating event. The victims and their families showed strength, courage and dignity in extreme circumstances. My team and I built up a strong level of trust with them by working until we quite literally were ready to drop at times and they put their faith in us. I feel privileged that my own circumstances put me in a position to help them.

Acknowledgements

My role in this work is nothing without the many friends, colleagues and organisations both in the UK and Pakistan who formed our team or supported it .I extend my thanks to all but a few deserve a special mention.

My colleagues in the British Association of Plastic Surgeons were receptive to our assessment of the situation and responded quickly to our request for more teams. This undoubtedly saved many lives and limbs.

Dr Amjid Mohammed (Consultant in Emergency Medicine, Huddersfield-Halifax) put together and lead our team through two relief trips in the aftermath of the NW Pakistan earthquake, followed by further trips to improve the quality of emergency medicine in the region.

Dr Huma Jadun and Dr Ghazala have worked tirelessly with our team and on their own projects to try to rebuild the shattered lives in the region. Without Dr Huma’s support our efforts would have come to little. Dr Ghazala found and funded a hospital for us when we had many patients in need of urgent treatment, but nowhere to treat them.

My father Dr Riaz Saeed (GP) swapped a peaceful and safe retirement for the mountains of NW Pakistan and has been an integral member of our team since. His experience and expertise was invaluable in Dec 2005. He, Dr Amjid Mohammed and Dr Saika Rahuja joined Dr Huma and Dr Ghazala to provide primary care to the most remote areas affected by the disaster. This work continues.

There are many more as the images below will convey.

Waseem Saeed

January 2008